Propaganda Design: An investigation into American and German WWII posters

Introduction

When contemplating propaganda, undoubtedly visions of war and politics arise. Arguably, propaganda played a vital part in the uprising and defeat of Nazi Germany throughout the Second World War. This research project will pay focus to American and German propaganda, in particu- lar, the posters used. Semiotic analysis will be undertaken to discover the influence of propaganda on the culture in which it was advertised, and how its employment of semiotic theory would have supported its success. Focus will be on discovering how propagandists are able to convince a na- tion into conforming to ideals, and how propaganda designs—by the likes of the United States, Office of War Information (OWI) and Nazi Germany’s, Ministry of Propaganda—had the power to manipulate and influence targeted audiences. It could be said that propaganda artists (or what could be referred to as visual communicators within twenty-first century), would evaluate their audience, using semiotic techniques, such as, psychology of relatable visuals and persuasive mes- saging, in order to appeal to, and delusion the receiver.

Development of Research

Propaganda is a form of biased communication, aimed at promoting or demoting certain views, perceptions or agendas. Not only does propaganda refer to it’s famous historical use—primarily associated with posters during the First and Second World Wars—it is a proven technique that still maintains pertinence within modern day culture. Propaganda is everywhere. Twenty- First Century advertising utilises such propagandising themes in a less ‘aggressive’ manner than what is commonly associated with war and terror. Propaganda, whether in reference to WWII, or Twenty-First Century advertising, promotes a sense of common cause and affinity; it can alter behaviours or influence beliefs—having the power to manipulate, deceive; even eradicate. It could be argued that the most sophisticated use of propaganda is within politics; especially within governmental campaigning.

Propaganda was applied for several affects during WWII. From pamphlets aimed at propagandising enemy soldiers (usually filled with conspiracies to make soldiers doubt their cause), to motivational posters aimed at encouraging civilians in their war effort (from harvesting their own produce, to more onerous work, such as, enlisting in the military). Various methods were explored to create propagandising materials—ranging from wartime information and basic instructions, to motivational messages and inspirational content. Conventional newspapers and posters were combined with modern methods such as film and radio, to produce a vast and influential campaign—plausibly a fundamental support to an allied victory. Propaganda could be referred to as the art of war—or particularly—the art of persuasion (Rhodes, Margolin, and Lewine, 1994, p.174). Its purpose often to persuade others of their greater military might, or favoured political status, and overrule the audiences’ judgement into alignment with the projected ideologies set out by the orchestrator. The propagandist will operate with the concept of multiplex visual and verbal messaging—which could further be defined as the practice of semiology. Semiotic theory can be exercised to analyse and understand the created—and the communicated—meaning behind visual and linguistic propagandising materials. The semiotics within culture and the inclusive bodies, has an immense and unconscious impression on persons judgements, reactions and consequently, actions. It could be suggested, that civilians and fighters, subsisting within the ordeals of the Second World War, were perhaps, unaware of the effect that the issued propaganda was having on their perceptions and cognitions. As a result of this, allowing them to be highly susceptible to such means. Semiology offers the tools to take apart an image, and trace how it works in relation to broader systems of meaning. (Rose, 2012, p.105). It’s only once the circumstances have returned to their usual state, and disturbances are settled, that we can analyse their significance and the repercussions caused by such occurrences.

Propaganda utilises semiotic practices in order to manipulate the cognition of an audience. These processes of semiological knowledge are harnessed as a means to convince the public of political ideals; furthermore, manufacturing them as appropriate systems or beliefs to be a party to. The Nazi ideology (Wippermann and Burleigh, 1991, p.11) and in particular, the aspired ideals of Adolf Hitler, were to achieve a ‘pure’; aryan race—free of the despised Jews and enemy defence. Such political motivations, along with psychological knowledge, work by manipulating its audience, through emotive connotations, such as themes of: guilt, morale, faith, and unity. Emotive codes are applied to suit appropriate consciences, lest to avoid the possibility for skepticism concerning the nations belief. Some methods would be harnessed to provoke feelings of responsibility within people. Nations were often brainwashed to take an unjustified accountability for governing actions. For instance, the use of blackmail and intimidation, as a means to ensure peoples cooperation. Despite this licentious strategy, it would be a mistake to produce propaganda with high moral conscience. “As soon as you…try to be many-sided, the effect will piddle away, for the crowd can neither digest nor retain the material offered. In this way the result is weakened and in the end entirely cancelled out.” (Hitler et al., 1998, p.181)

People are familiar with Hitlers egregious political and racist ideologies for an Aryan race. It is perplexing how such heinous ideals were accomplished and accepted by an entire German nation. It could be argued that the use of semiology within Nazi propaganda helped to encourage these objectives into acceptance. “Ideology is those representations that reflect the interest of power… ideology works to legitimate social inequalities. Semiology…is centrally concerned with the social effects of meaning; hence the description of semiology as “laying bare the prejudices beneath the smooth surface of the beautiful”” (Rose, 2012, p.106-7). The notorious events of WWII expand on the notion of laying bare the prejudices (Rose, 2012, p.106-7), for such acts were once perceived as ‘ordinary’. These affairs are, somewhat, dismissed within Twenty-First Century culture. By exploring the historical use of semiotic theory, the intentions behind propaganda can be revealed and explanations can be made as to how such adverts were able to convince nations into accepting such abnormal events as normal ones.

“Propaganda agencies drew on the expertise of advertising, which in turn had advanced between the wars by applying theories from behavioural psychology and the social sciences. The Allied governments developed the practice of carefully monitoring the effects of propaganda, using new market research surveys. These techniques were subsequently adapted by politicians for their election campaigns, and marked a permanent shift towards the image-conscious politics” (Clark, 1997, p.105). In order to reverse peoples social and moral cognitions, philosophies on how to carefully and effectively do so, have to be obtained and exerted over time. The intention of propaganda posters is to attract attention and change cognitions of those in opposition to, or doubt of, the political agendas; opposed to “educating those who are already educated” (Darman, 2008). “Political power comes from changing people’s minds, not conforming those of the people who already agree with you.” (Baldwin and Roberts, 2006, p.128-129) Political leaders and advertising experts were well aware of the significance semiotics holds to produce persuasive propaganda, and how such psychological theories influence social factions. WWII propaganda was, initially, published to the home front and overseas public as a means of disseminating wartime information. However, programmes of propaganda—especially in poster form—were soon mass produced to an unparalleled scale, to ensure publics continued trust in policies. The cheap accessibility to generate posters meant it was an uncomplicated yet powerful psychological aid (Darman, 2008). This administration of data later developed into meticulous censorship of media broadcasts—undoubtedly for bureaucratic gain and advancing of political ideals. The US and Nazi government produced vast; rigorously censored war imagery—implemented and replicated across multiple areas of media. “Newspapers and magazines were supplied with thousands of photographs from war correspondents and combat photographers, but before reaching the press these were vetted by a process of censorship which filtered out photographs of a wide variety of ‘unsuitable’ topics. It was this process which transformed the documentary evidence of war into propaganda.” (Clark, 1997, p.111) For a piece of propaganda to be successful, an understanding of semiotics should be ascertained for the sake of persuasive campaigning and censored information to take effect.

The use of semiotic theory can be divided into subcategories, such as, signs and symbols. Sign is a basic unit of language, in which there are two parts: the signified and signifier. The signified forms an understanding of a concept, or of an object (Rose, 2012, p.113). The signifier represents sounds or visuals adhering to the signified notion (Rose, 2012, p.113). Symbols within semiology can be defined as obtaining denotive and connotive levels of meaning. Denotation describes something in its initial and often most literal form, and is fairly easy to decode (Rose, 2012, p.120). Whereas, connotive signs carry a range of higher-level meanings (Rose, 2012, p.120), which rely on the context and peoples interpretations for its representation to be attained.

WWII posters would address different political and cultural issues, such as: encouraging production, enlisting in the military, inducing feelings of national pride and morale, fighting for freedom, evoking fear in the enemy, connotations of guilt, and providing social security—to name some. Mentioned themes were often presented and repeated within the wording and sustained use of images. “The most famous was the theme of “careless talk,” the notion that enemy spies were everywhere and that a seemingly innocent conversation could be overheard by them, leading to the deaths of service personnel at the very least.” (Darman, 2008). This problem of careless talk is frequently used within OWI’s posters (Bird and Rubenstein, 1999, p.44), and—less literally; rather metaphorically—promoted within posters like “Someone Talked!” and “Wanted! For Murder” (Ramsey, J. 2016, p.13).

When dissecting the poster, “Someone Talked!” (Figure 1), many diegesis can be interpreted. This poster simply denotes a vision of a man in water. However, the connotive signs—provoked by the language within the poster, and supported by the tone of image—carry a variety of higher-level meanings. These higher-level meanings induce feelings of sorrow toward the man, whom appears to be drowning. Fear of responsibility and a sense of helplessness could be experienced due to inability to save the figure; therefore provoking guilt within the audience. This conclusion can be assumed due to the visuals context and the choice of language. The text compliments the image through use of—the semiological term—anchorage, which “allows the reader to choose between what could be a confusing number of possible denotive meanings” (Barthes, R., 1977, p.38–41).

Language holds great importance when it comes to the translation of meaning, and works as a relay-function (Rose, 2012, p.120) for the transcription of intent. Signs are highlighted with a basic unit of language, integrated in their practice (Rose, 2012, p.113). In this case (Figure 1), the signified concept happens to be an adult male—whom is almost fully submerged in water—with his hand raised above the surface; pointed at the viewer. The theory of referent (Rose, 2012, p.113) explains the connection between the signified and signifier. This crucial distinction between signs ensures the image is not just elementarily assumed as a male in the water, but identified as a soldier drowning—feasibly due to exposure by the enemy artillery. The propagandist will use referent systems (Rose, 2012, p.129) to construct a framework—referring to pre-existing insight on how to produce effective outcomes—to form the structure of the advert. Such frameworks utilise professional codes as a guide to producing formats and appoint the most appropriate and effectual images to stage the debate (Rose, 2012, p.128). Once a propagandist deciphers and analyse’s an audience to focus on, a design can be established with encoded connotations that transfer the signified meaning effectively (Rose, 2012, p.128). This theory of professional coding is a supporting mechanism when envisioning the impression on the target audience.

Representations of manner (Rose, 2012, p.115) are made evident within the characters facial and bodily mien. There is an angry and haunting look within his eyes, supported by the action of the pointed finger. The sturdy point could be a portrayal of masculine strength and signify passive aggression, by literally and metaphorically pointing the finger at the targeted audience. This notion of blame, suggests use of a schematic approach to design—a scheme also identified within Nazi propaganda through the singling out of enemies, and especially of Jews, whom were blamed for Germany’s ills (Darman, 2008) would be directed. These themes of culpability within propaganda are reiterated in its (Figure 1) approach to singling out the viewer with the convincing slogan “Someone Talked!”. The rhetoric of the image (Barthes, R. 2009) encourages the audience to question their responsibility, particularly proposed by the pronoun “someone” as a potential answer to the title.

Linguistic systems are vital propagandising tools; therefore the selection of words and phrases are to be carefully considered in alignment with artworks, as “Words carry emotive connotations, implying varying guilt attribution, and can serve to neutralize or justify (in-)human acts. If a source can bring a medium to adopt its language, it has already won an important psychological victory” (Schlesinger, 1991, p.24). It could be said that Figure 1 uses such techniques to target American civilians—likely to be the women on the home-front. A common, misogynist view perceives females as the more sensitive and compliant gender. The premise that women are highly susceptible to emotive messaging corroborates their vulnerability to the effects of propaganda. However, motives for vengeance are dubious based upon the insight that Figure 1 is to be seen by Americans. It seems as if blame is groundlessly imposed on US people. It could be argued that a more realistic, and justifiable target would be the enemy Nazi’s.

Direct addressing of the audience, through visual and linguistic techniques are similarly used within the famous WWI portrait of Uncle Sam, entitled “I Want You for U.S. Army” (Figure 2). Themes of patriotism are highly propagandised within Figure 2 as an aid to encourage US military recruitment, or “to convince the American public that the millions of servicemen being sent to Europe and the Pacific were fighting a worthy cause.” (Darman, 2008) Patriotic posters often made use of emotive symbols to represent nations identity and political status, by characterisation of physical forms, repeatedly seen on the uniforms and flags in the posters (Darman, 2008), such as, Stars and Stripes in the United States (seem within Figure 2) and the Swastika in Nazi Germany (Darman, 2008). It could be suggested that techniques that directly address the audience, evoke emotive themes of patriotism. The success of Figure 2 was plausibly an inspiration for the design of Figure 1.

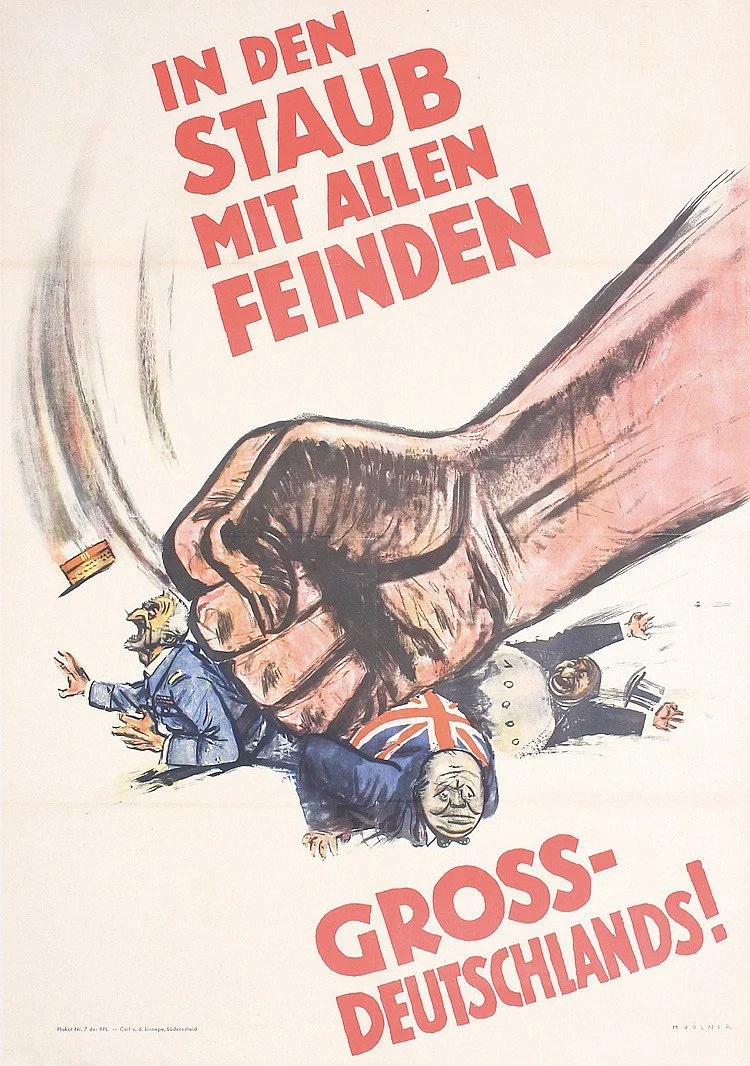

Whilst American propaganda played on the notion of manipulating allied cognition, German propaganda typically used techniques, such as, demonisation and weakening of the opposition, glorification of soldiers, and portraying greatness as a nation. Embodiments of unity amongst Germany often envisioned by Hitler as the ex-serviceman (Darman, 2008). Nazi propaganda would often present Hitler and his soldiers as strong; heroic individuals. This theme of a ‘better’ nation, is accentuated within Figure 3. The poster illustrates a masculine, and powerful looking fist crushing Nazi enemies: Winston Churchill (British Prime Minister), Charles de Gaulle (French President) and a Jewish-man. This demonisation of enemies connotes Germans, self-perceived, superior strength, through ease to destroy entire nations with one fist. Whereas, the US would typically present soldiers in fatal situations (like demonstrated in Figure 1). Interestingly, all three figures utilise a males hand as a mean to metaphorically connote converging meanings and provoke emotions. Both approaches can be deemed effective, but it could be argued that Nazi Germany had the upper-hand when it came to manipulation. The Nazi’s were rigorous users of propaganda, and somewhat, abused this tactic to its fullest. It could even be said that Nazi’s turned propaganda into a religion (Darman, 2008), based on the premise that Nazi material was capable of indoctrinating such aberrant views on the German people.

Figure 3 exaggerates Germany’s power over other nations in a bias, boastful light. Although a dishonest advertising, it would, however, be a mistake to produce propaganda addressing respective sides. Its prejudiced nature is what constitutes such persuasive means of promotion. A successful technique for a bias outcome is to ensure limited points are made, in which these specific points are obvious to the public. To be bias is to be one-sided, however, if both the American and German propaganda use such discriminatory arguments within their propaganda, then who is right? This question addresses the theory that propaganda trials with the concept of deceit— through, not only manipulated and exaggerated truths, but—via the use of lying disguised as honesty. Fabrication of context was an extremely useful asset to propagandising the audience. “In the big lie there is always a certain force of credibility…nations are always more easily corrupted in the deeper strata of their emotional nature than consciously or voluntarily” (Hitler, 2010). Everyone articulates little lies, but “It would never come into their heads to fabricate colossal untruths, and they would not believe that others could have the impudence to distort the truths so infamously.” (Hitler et al., 1998, p.181) German posters often portrayed there enemies, especially the Jews, in the worst comprised light. Whereas, ‘pure’ Germans were idealised as blonde and blue-eyed; handsome and physically fit (like the strong, masculine hand in Figure 3).

The political ideologies of America and Nazi Germany, harnessed the power of the media and semiotic techniques to create propaganda that surely changed the world. The media, is undoubtedly, a platform for disseminating news regarding world affairs, and has a huge impact on social and political culture. “The media are supposed to be public watchdogs, applying their investigative powers to restrain and critique government activity” (Schlesinger, 1991, p.79) however, in reality, the media functions as propaganda machines on the government’s behalf (Schlesinger, 1991, p.79). Due to the awareness that the government controls information before it meets the public, implies that it has formerly undergone strict censorship. This applied coding is a technique proven to advance political ideologies.

Through the analysis of various visual and textual examples, I investigated how the tactical employment of semiology within WWII US and Nazi propaganda, had the power to influence the social workings of culture. Evidence demonstrates how semiotic theory is employed to manipulate and influence the viewers cognition in alliance with planned ideals. Successful propaganda effectively applies and exploits the investigated semantic techniques in support of political campaigning. My research observes studied methods of deception, through the telling of partial truths and the omission of others (Galloway, Reynolds, Danver, and Steven, 2015). Such themes, allow for the propagandist to directly shape opinions, manipulate cognitions, and alter behaviours in fraternisation with invented ideologies. Conclusion informs, that the harnessed and conscientious handling of the established semiotic tools, make propaganda a substantiated; powerful weapon of war!

Figure 1. Frederick, S. and Office of War Information (1942) Someone talked! [Poster]

Figure 2. Flagg, J.M. (1917) I Want You for the U.S. Army [Lithograph].

Figure 3. War posters (1942) In Den Staub Mit Allen Feinden Gross-Deutschlands! [Poster]